CME Closes Trading Pits in New York & Chicago

Former floor traders reminisce about their days of open outcry trading in Chicago and New York.

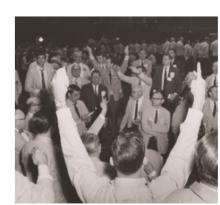

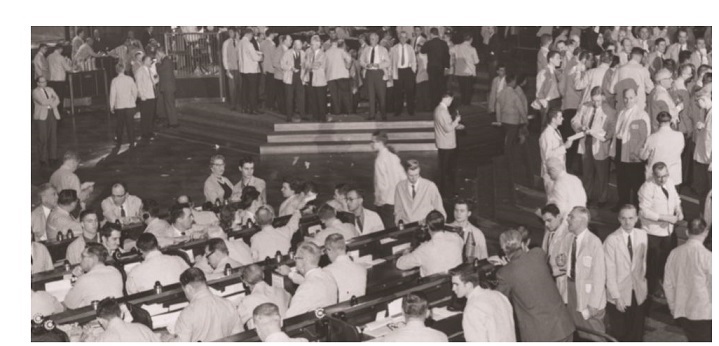

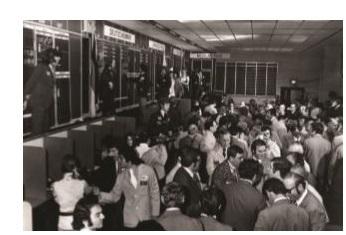

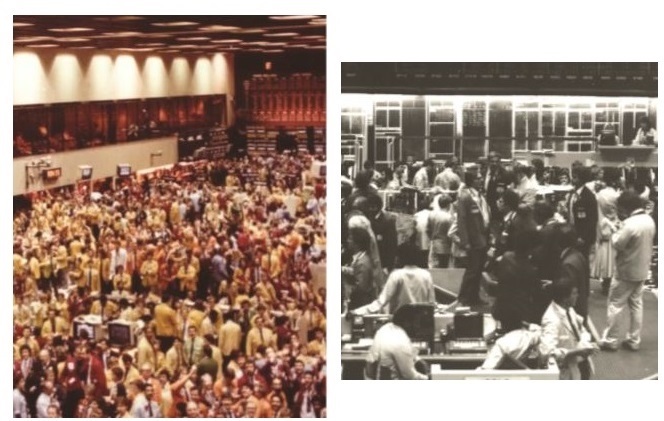

This summer, CME GROUP closed open-outcry trading for nearly all of its futures markets in New York and Chicago. That brought an end to a 167-year tradition of price discovery via a raucous group of mostly men crowded into pits and gesturing with their hands to buy and sell a wide range of commodities and financial instruments.

The vast majority of futures trading at CME is now conducted electronically. While open outcry continues in the exchange’s options pits, many see these markets also shifting eventually to electronic trading.

Today’s electronic markets are vastly larger and more efficient than what used to exist on the trading floors in New York and Chicago, but industry veterans say open outcry served the industry very well for many years. The floors may have appeared to be disorderly and chaotic, but they nurtured many generations of extraordinary traders who helped transform the futures markets into a vital part of the global economy.

Open outcry trading began in the mid 1800s as a centralized place where farmers could sell their crops, such as corn, to producers and other buyers and lock in prices in advance. The Chicago Board of Trade, along with other markets in Minneapolis, Kansas City and New York evolved over the next 100 years to include settlement and formal clearing systems, multiple delivery points and cash-settled contracts.

The biggest transformation, however, has been the move to electronic trading, a transition that has been taking place for more than two decades in the U.S. and elsewhere around the world.

Floor traders worked very differently than electronic traders. They used hand gestures, paper orders and they shouted. But it is this type of trading that many credit as one of the most critical market innovations that helped transform futures markets into a vital part of the global economy.

“These are the people who changed the world,” said Richard Schaeffer, former chairman of the New York Mercantile Exchange, who helped lead the exchange to electronic trading.

“What we built afterward with electronics could never have been achieved without their [floor traders] work for the many, many years that they were the most important element,” said Leo Melamed, chairman emeritus at CME Group.

A Family Affair

For many floor traders open outcry trading was a family business. It was not uncommon for exchange seats to be passed down through the family for multiple generations and for siblings and family members to work side-by-side.

Speaking fondly of his days on the floor, former CBOT Chairman Charles Carey said: “My grandfather got a job as a runner in 1903 and he started trading after World War I. My father came down there in 1948 after World War II. His oldest brother was also a member of the exchange. He’d been a member prior to World War II, left for his service and came back. So I joined in 1978 and I have been a member ever since.”

Lee B. Stern, president of Lee B. Stern & Co. and the longest active member of the CBOT, spent 50 years in the pits. Stern started as a runner after he was discharged from the Army Air Corps in 1947. He said it meant a great deal to him to be part of the floor community. “I ended up with my three sons and daughters all with ownership trading rights …that helped the family get started in the business,” he said. “I can’t say that it hasn’t been a great run for everybody.”

The floor environment also cultivated a unique bond among traders. “You’re shoulder-to-shoulder with people for six hours a day and seeing all kinds of emotion and it’s a very competitive environment,” said Larry Shover, chief investment officer at SFG Alternatives, who began trading in 1983. While it is competitive, he says it is also truth-telling and self-policing. “If there were something somebody didn’t like about me, they would just say it and vice-versa. So it actually is very freeing in a way,” he added.

“It’s the only business in the world where you can go toe-to-toe with somebody and say anything you ever wanted and then go for lunch or coffee,” said David Greenberg, president of Schaeffer Greenberg Advisors and a former Nymex board member and executive committee member.

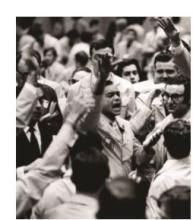

On the floor success wasn’t about titles or education. What made a successful trader was quick thinking, being visible and having a loud voice. Successful traders also could “read” the market. When volume and intensity picked up outside the open and close, positions would be adjusted because it was understood that news would follow shortly.

“There really was no hierarchy or chain of command. Everybody was doing basically the same thing, so they were your peers,” said Peter “Zap” Chelemengos, who began at the CME in 1976 as a runner and eventually had a gold membership.

Controlled Chaos

To many, the noise, the crowds, the fast pace and the constant adrenalin rushes were a powerful attraction.

There really was no hierarchy or chain of command. Everybody was doing basically the same thing, so they were your peers.

Peter “ZAP” Chelemengos

“As people came in, it was like the hum started to build and then when that bell went off and the grain markets opened, pandemonium just broke loose,” said William “GRU” Gruzynski, said ‘I am home.’ Within all this chaos there was a certain order built inside,” he said.

In the pits hand signals were the way people bought and sold contracts. A simple tap with fingers to the forehead would signify multiples. A movement to the side could mean hundreds. For the most part the system worked.

“You had to be very careful when you were giving quantities, that they were easy to read,” said Chelemengos.

Amid all the noise, a good trader would thrive. “I knew exactly who was yelling from across the trading pit. You were so attuned to it you could hear someone’s voice and know exactly who was bidding and who was offering. So as crazy as it was, it really was organized chaos,” said Kevin Grady, president of Phoenix Futures and Options.

Grady planned to become an attorney, but decided Nymex was his home after getting a job as a runner in 1984. Grady recalled hiring voice coaches and yelling into a pillow during vacations to keep his voice in trading shape. “If you came back after being away for a week or two and not yelling, you would lose your voice within two days and you wouldn’t be able to yell or trade for three or four days until your voice got acclimated again,” he said.

Being tall or having a louder voice was an advantage for some traders, according to Scott Shellady, a former commodities broker at the CBOT and now a senior vice president of derivatives at TJM Investments. Shellady, who stands over six feet tall and played football in college, stood out even more on the floor by wearing a cow-patterned trading jacket, a tradition his father started in the early 1960s.

“There was a value to someone my height and my size,” said Shellady. “You had to be able to project yourself, attract attention, get your customer orders done and filled in a timely fashion.”

Events Remembered

For many traders, their most memorable days range from World War II, Gorbachev’s visit to the floor, the Soviet grain embargo, the 1987 market crash, to a trade that brought about a big fight or the first moment they stepped into the pit. For Nymex traders, the September 11 attack was one of the most significant events in the history of the floor. Not only did they lose members of their trading community, but the way they pulled together to reopen the markets was truly remarkable.

“I will never forget looking out the window after the first plane hit and seeing the image of the plane that had gone into the building,” said Greenberg. He explained how the Nymex board gathered by phone that night to discuss what needed to be done to get the exchange up and running in a matter of days. “We were the first exchange to open on Wall Street,” he said, explaining that Nymex members and staff, arriving by boat, worked alongside contractors around the clock to get the infrastructure back up and running. “It was a very proud time of my life to look back and say that we were part of that.”

Evolving Over Time

Adapting to change is nothing new to floor traders. The 1970s and 1980s were a period of extraordinary change with the introduction of futures on interest rates, currencies and stock indices as well as options on commodity futures. But trading skills are transferrable—most traders didn’t care what the product was, they just wanted to trade.

“Imagine traders that used to be hog traders or corn traders and suddenly they are trading Swiss francs. They knew how and they learned because I guess it's in their blood and it worked,” said CME’s Melamed.

Adapting to a different manner of trading has proven more difficult, however. Over the years technology has made its way into the trading pits as traders began using electronic devices to take orders and eventually computers made their way to the floor in various forms. But CME and Nymex held onto open outcry for much longer than other futures exchanges such as the London International Financial Futures Exchange.

“I was one of the early adapters here at the Merc, probably the first person to bring a computer down onto the trading floor. And then we actually had to remove it because they weren’t approved at that time. So we ran our computer from upstairs and ran the wires downstairs,” Gruzynski said.

As people came in, it was like the hum started to build and then when that bell went off and the grain markets opened, pandemonium just broke loose.

William “GRU” Gruzynski

Many in the trading community have adapted well, however, and appreciate the benefits of electronic trading. “I’ve been fortunate that I find myself today trading larger than when I was in the pit,” said Stern. “I was a fairly large trader [on the floor], but nothing compared to today.”

A move to electronic trading in the U.S. became all the more likely after Deutsche Terminbörse, the predecessor to Eurex, established an all-electronic exchange in the late 1980s. “I’ve been able to survive because I do love technology and I’ve adapted with it and I think that’s important,” agreed Shellady, who was trading at the London International Financial Futures Exchange 18 years ago in 2000, when the exchange overnight shifted to electronic trading. “It’s like taking a band-aid off. In Chicago, we’ve done it one hair at a time; in London they just ripped it off in one day. That forced people to get out there in one day rather than mill around and miss opportunities,” Shellady said.

Going Electronic

Madeline Boyd, a former trader and the only woman to have served on the Nymex executive committee, explained that it was a difficult decision for the board to allow electronic trading alongside open out-cry trading. We knew we had no choice. Our main competitor was gaining market share daily,” she said.

Schaeffer agreed that Nymex would not have survived if it had not made the decision to allow electronic trading alongside open outcry, particularly as other competing exchanges were operating in an all-electronic fashion. “If we didn’t do it, and I was chairman at the time, the Intercontinental Exchange would have had our lunch. We would not have been a competitive exchange,” he said.

Even so, many in the industry miss the openness, the central location of trading, the camaraderie and the adrenaline of open outcry.

“I think the younger generation will see my cow jacket in a shadow box on the wall and not believe that I wore pajamas and yelled and screamed every day to make my money,” said Shellady. “It will probably seem really silly to people in 30 or 40 years, but it actually served a really good purpose.”

“It provided a lot of interesting information to buyers and sellers,” said George Gero, now with RBC Wealth Management, who started trading metals in New York in 1964.

And while open outcry in the U.S. futures pits is now largely a thing of the past, it was one of the key innovations that helped put futures markets where they are now.

“It’s that kind of spirit, that innovation, that will continue. You can’t take that away from the trading community,” said Melamed.