A recent news article caught my attention and highlighted the power of our markets to change the human condition. While a U.S. story, it has implications for all markets globally. A few months ago buried in the business section of the newspaper read a headline—the U.S. had become the world’s largest producer of crude oil and a net exporter of petroleum for the first time in 75 years, thanks to an unprecedented boom in oil production over the last decade.

This story seemed to go largely unnoticed, despite the fact that the last 50 years of foreign policy had revolved around securing foreign sources of petroleum to the tune of two wars and billions of tax dollars spent. How did this massive geo-political and economic shift occur without much notice?

This milestone didn’t come out of nowhere. U.S. production has been on the rise for several years, driven by capital investments and technological advances that have revolutionized our ability to extract oil and gas from shale formations. But it’s worth taking a moment to put this milestone into context and consider its causes.

Just think back to where the oil industry was a decade ago. In 2008, the developed world was at the mercy of OPEC nations for their energy needs and the price for crude oil skyrocketed to $140 dollars per barrel. This extraordinary increase in price ricocheted through the supply chain and reverberated through the global economy.

In the U.S. as those price increases hit home, public opinion followed accordingly. Homeowners complained about the price at the pump and the cost of heating their homes. Airlines complained about fuel costs. Gas stations complained about lost sales. And they all complained to Congress.

I was Acting Chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission at the time. I was called up to Congress more times than I care to remember and asked to explain why the oil price was so high and what could be done to bring it down. Root canal would have been more fun.

A popular opinion at the time was that the futures markets were broken, and Congress needed to rein in speculators. As the head of the CFTC, I could see from the trader data that the markets were doing their job. The oil industry was operating at full capacity, the Chinese economy was sucking up excess supply, and the markets were anticipating a global shortage. At cocktail parties, people were talking about the “Peak Oil Theory.”

Like many commodities, oil prices go through cyclical price swings as the industry trends from over-production to under-investment. It’s tempting for politicians to try to dampen that market cycle in the short term through subsidies, price controls or even trading bans. These attempts to regulate prices often mask the powerful price signals that markets are trying to send to investors regarding where to put their capital to work.

Ponder: Would the U.S. have become the largest producer of crude oil today if markets a decade ago weren’t able to reflect these prices?

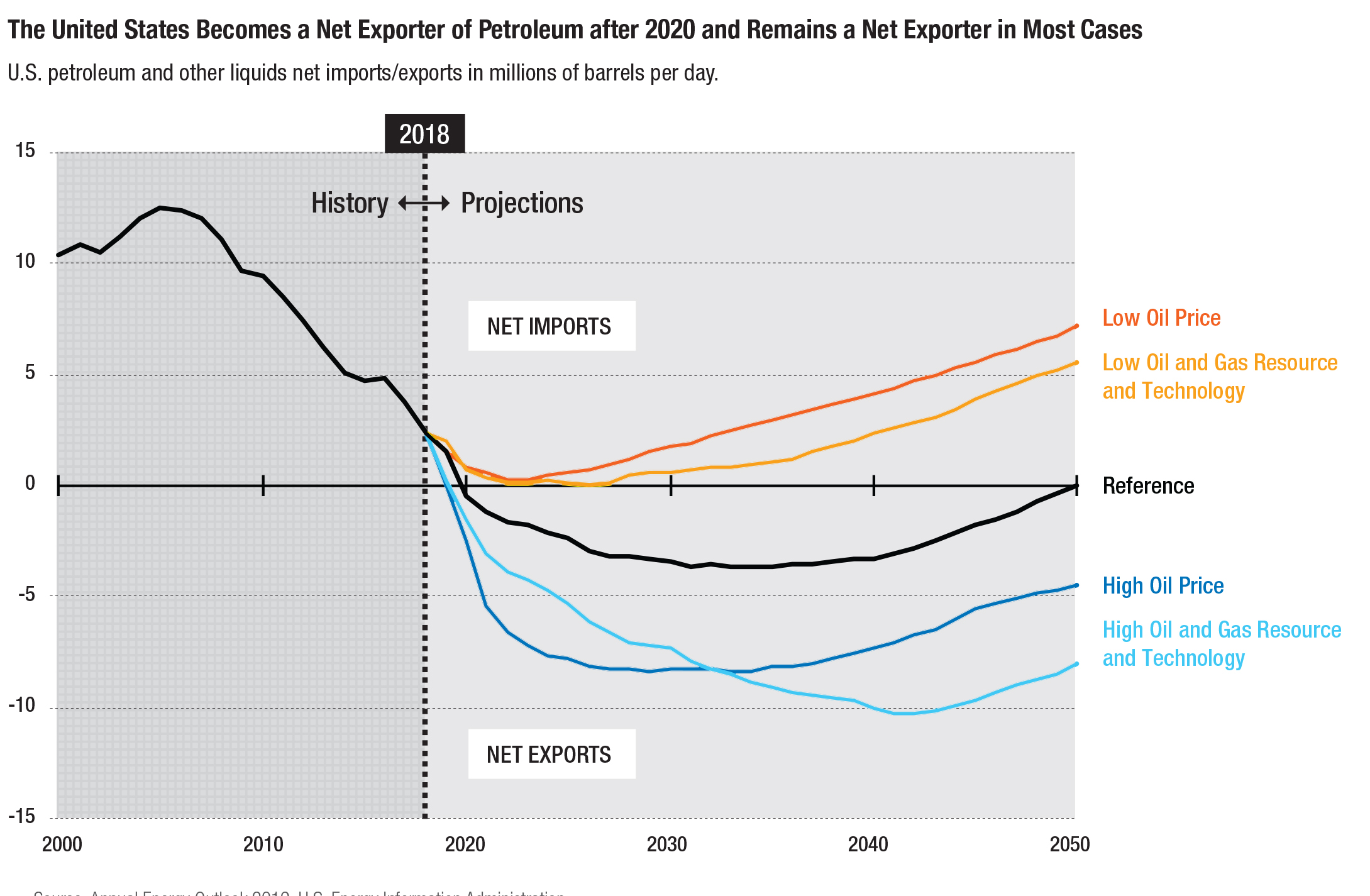

The chart helps shed some light on this. Those high prices spurred innovation in the oil field that we have not seen in generations. Millions of barrels of oil and thousands of cubic feet of natural gas were brought to market because it became economical. Shale-rich North Dakota had the lowest unemployment in the country for a time. Those high prices also stimulated interest in alternative sources of energy, and since 2008 investment in renewables has been just as extraordinary as the investment in oil production.

Demand also changed dramatically. Today there are more electric vehicles than ever before, people are moving closer to city centers and driving less, and buildings are better designed to conserve energy.

Remember the old saying in economics? The solution to high prices is high prices. When markets reflect high prices of such commodities as oil, or even corn or interest rates, they are sending powerful signals that supply and demand are out of balance. The solution is not to shoot the messenger; it’s to allow oil drillers, farmers and entrepreneurs to put their derricks, seed corn and capital to work to bring markets back into equilibrium.

Despite this, we should not lose sight of the enormous impact of high prices on the pocketbooks of real people. The surge in oil prices in 2008 was extremely painful for many businesses and consumers. It’s no wonder that so many politicians heard this concern and tried to do something about it.

That’s why it’s important that markets operate within a framework of rules and regulations that uphold their integrity and keep them free of fraud and manipulation. Smart regulation makes us confident that the markets are reflecting the true levels of supply and demand.

Today there is a growing tendency to blame markets for many of our society’s problems—from food shortages to income disparities to high commodity prices. Markets are likely to come increasingly under attack.

In my view, we should be looking to markets as part of the solution to today’s challenges—not as the focus of our ire. Blaming markets for high prices is like blaming a thermometer for it being hot outside. That said, it is the job of all of us, regulators and industry alike, to ensure that no one is holding a match under the thermometer. The enormous power of markets comes with an equal industry responsibility to be its stewards. Let’s harness this collective wisdom for the support and betterment of our markets.

Walt Lukken is the president and CEO of FIA.