The U.K. referendum raises difficult questions for the future of London's clearing infrastructure.

If there is one thing that is certain about Britain’s referendum on its future relationship with Europe, it’s that the referendum has delivered uncertainty by the bucket load. While new U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May has declared “Brexit means Brexit,” what form that exit takes, when and with what impact remains far from clear.

Those who voted to leave the EU – 52% of voters to 48% voting to remain – appeared to anticipate immediate results. The results they got, though, may not be what they expected – the resignation of David Cameron as prime minister, political infighting in the race to find his replacement and an immediate spike in volatility. Sterling fell to its lowest level against the U.S. dollar since 1985 and 10-year gilt yields hit record lows. Additionally, in a bid to ward off a Brexit-triggered recession, the Bank of England cut interest rates to a record low of 0.25% and boosted its quantitative easing scheme with an extra £60 billion to buy government bonds and drive down gilt yields, another £100 billion to encourage banks to lend cheaply and a pledge to buy £10 billion of corporate debt from companies that make a contribution to the U.K. economy.

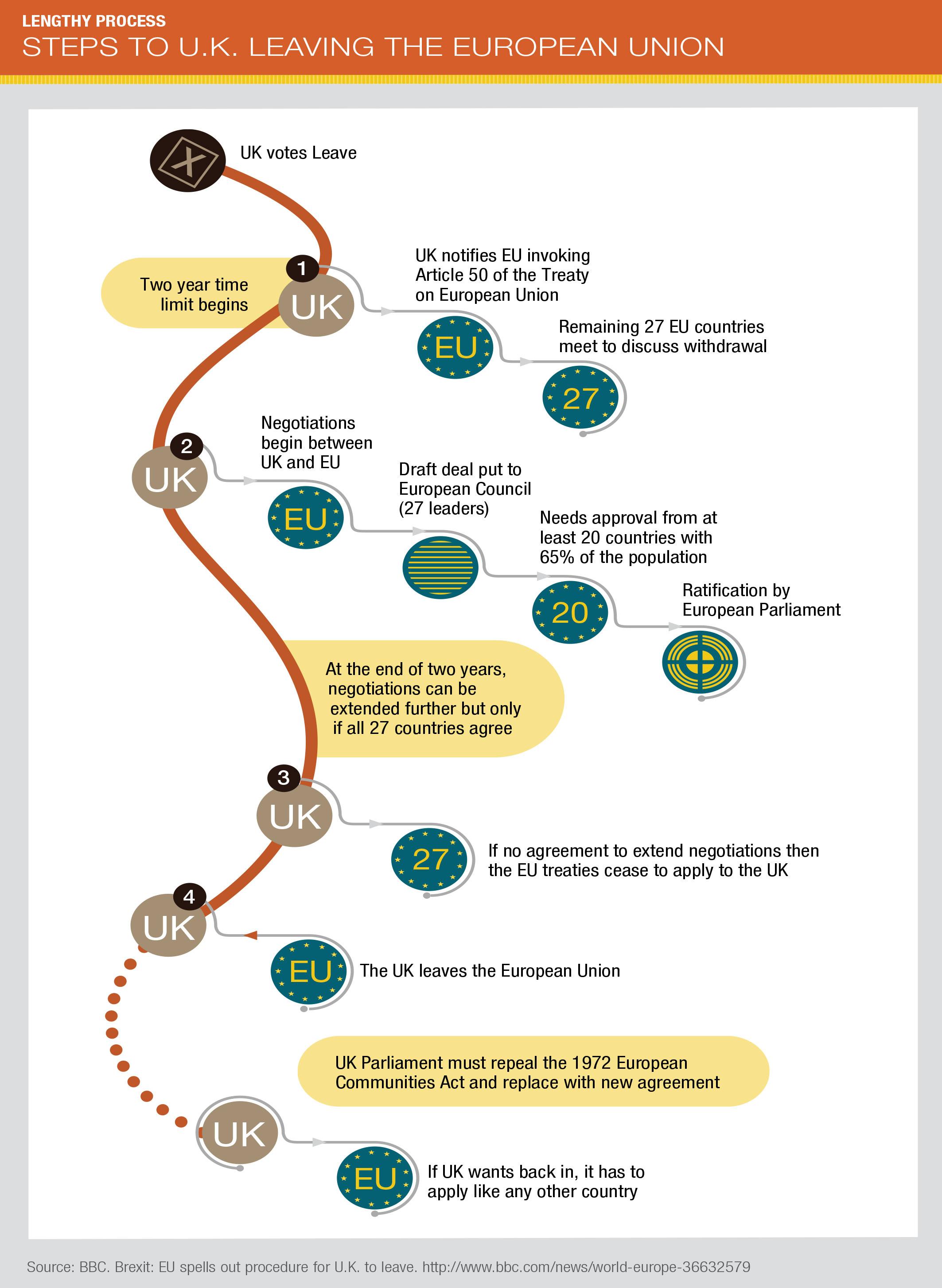

Lengthy Process

Aside from these steps, however, we are none the wiser about what form of relationship the U.K. will have with Europe in the future and how that will impact financial markets generally and the derivatives industry more specifically. Furthermore, that lack of clarity is likely to continue for some time as May has declared that Article 50–the mechanism for triggering an exit from the European Union–will not be invoked before the end of this year. There will then follow a period, expected to take two years, during which other EU member states will negotiate the terms for the U.K. to leave (see "Lengthy Process" diagram below), so that in reality Brexit could be pushed back until 2019.

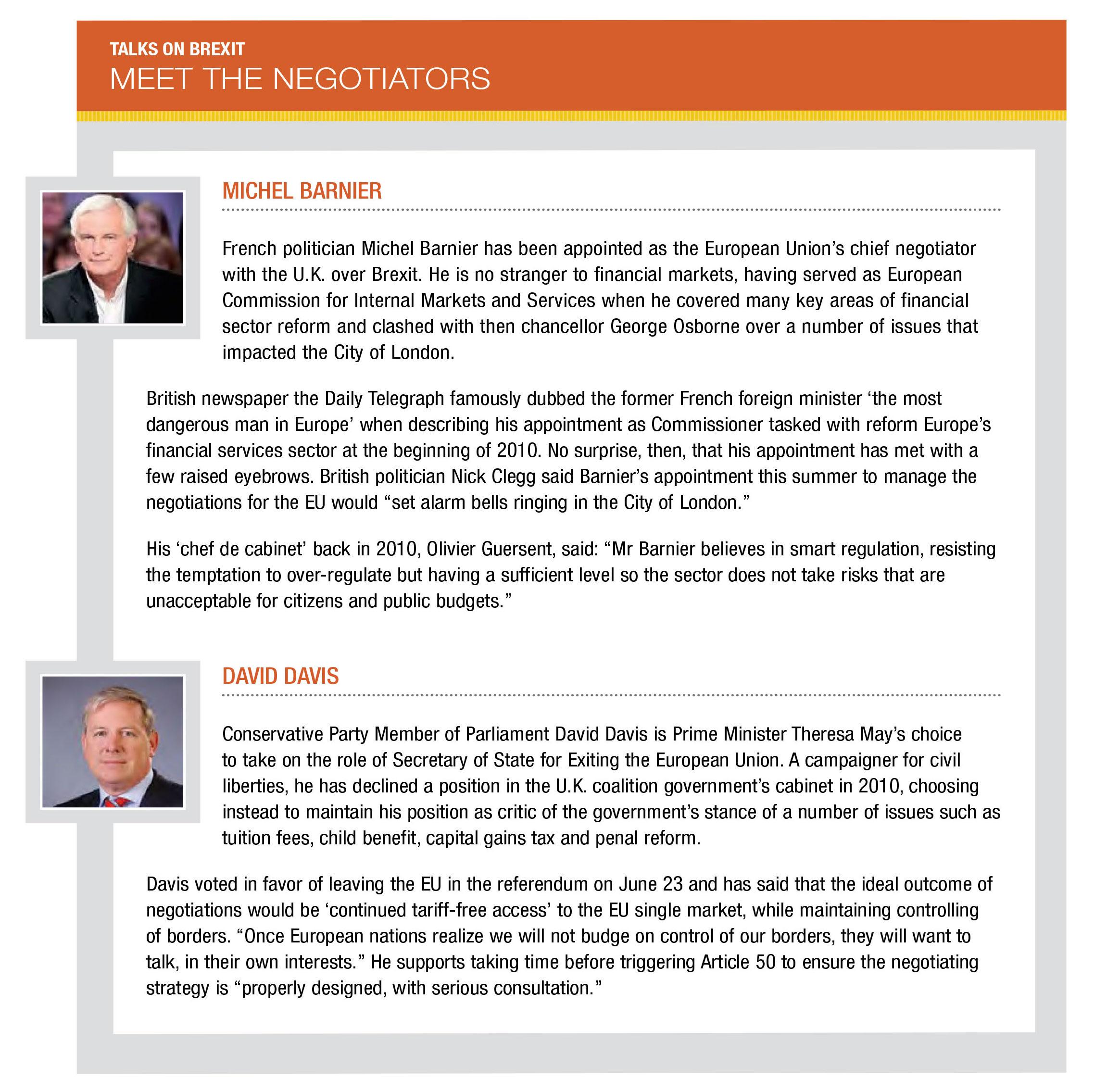

One reason for the delay is that much restructuring of U.K. government departments will be required to enable the negotiations to take place. It has been reported that David Davis, the minister in charge of Brexit, had, by the end of August, fewer than half the 250 European experts he needs to help the discussions, while Liam Fox, the International Trade Secretary, had fewer than 100 of the 1,000 he needs.

None of this has prevented speculation of what form of relationship the U.K. could establish with Europe for the future. The key aim, for most in the U.K.’s financial markets industry, is to maintain the passporting rights currently enjoyed by U.K. firms as being part of the EU.

The U.K.'s power market could suffer as a consequence of no longer being part of the so-called market coupling with continental Europe.

What remains unclear is how to preserve U.K. firms’ EU passporting rights: following the statement by Germany’s Minister of State for Europe, Michael Roth, that “free access to the internal market is only possible when all four of the fundamental freedoms are respected, including the free movement of labor,” the U.K. Prime Minister, Theresa May, reiterated that curbs on the current free movement of EU citizens into the U.K. are a red line in future negotiations with the EU. She has since said that the U.K. will have “some” control over EU migration after Brexit, so it is unclear quite how the U.K. government ranks the competing objectives of single market access versus immigration control.

Meanwhile, U.K. regulators emphasize that the country remains subject to existing regulations, including those from the EU, until the exit has been negotiated and completed. Andrew Bailey, the new chief executive of the Financial Conduct Authority, told a London conference recently: “I would emphasize that the U.K. remains a member of the EU until such time as things change, and so all of our rules continue to apply whether they originate from the EU or not. Likewise, we will continue to implement EU legislation until the future is clear, something that is again a legal requirement.”

This means that U.K. financial institutions will have to continue to implement MiFID II, which will come into effect in January 2018, even if they are no longer subject to it a year later.

In parallel, firms may have to prepare for whatever new regulations domestic regulators put in place to allow the U.K. to operate on an equal footing globally. This is where many of the industry’s unanswered questions remain. For example, will the U.K. be considered a “third country” under EU legislation as a result of Brexit? Can some sort of grandfathering be agreed? Must the U.K. embark on its own equivalence discussions with the U.S. and other third countries?

Specific areas of concern center on central counterparties and trade repositories. U.K. CCPs will potentially need to seek recognition under EMIR, unless their EMIR authorizations can be grandfathered as a part of the withdrawal agreement.

Meanwhile, the markets await clarity on whether the European Central Bank will tear up its settlement with the Bank of England on the ECB’s CCP location policy, such that only CCPs located in the Eurozone will be permitted to clear euro-denominated derivatives. If that were the case, how would trades already cleared on non-Eurozone CCPs be handled?

Clarification is also sought on the treatment of U.K.-based trade repositories and whether they will need to seek recognition under EMIR, even if they are already registered.

Additionally, U.K. trading venues and CCPs will want guidance on how to continue to avail themselves of the non-discriminatory access provisions in MiFIR relating to access to trading venues, CCPs and benchmarks.

Other questions are emerging as markets begin to digest the potential impact of the U.K.’s exit from Europe. One such issue regards the future development of a pan-European power market, which was designed to connect the U.K. power market to that of the continent as part of a broader plan to maximize efficiency and create economies of scale across the entire system.

Operating as one market could give the EU great negotiating power when securing deals on input fuels–which became an issue in January 2009 with the Russia-Ukraine natural gas crisis. The U.K.’s power market could suffer as a consequence of no longer being part of the so-called market coupling with continental Europe.

Brain Drain

Of course, it is not just the U.K. that will be impacted. The EU itself could lose out from the withdrawal of the U.K., which has helped shape regulations such as EMIR, MiFIR and MAR. It could also suffer from the loss of expertise within the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) that were established in 2010 such as the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and the European Banking Authority (EBA).

“The U.K. plays a strong role in these authorities in terms of their technical input, physical resources and market expertise,” FTI Consulting said in a recent report. “Decreasing U.K. influence in the ESAs as a result of Brexit could have significant effects on the final content of legislation as well as on the way European supervisors agree to apply the rules.”

The U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority is widely recognized as a major driving force behind ESMA. Indeed, ESMA’s Executive Director Verena Ross joined from what was then the U.K.’s FSA, with years of experience there and at the Bank of England. FCA has also provided much of the knowledge required to draft large parts of MiFID II. “Staff at [the FCA] have been seconded to ESMA, and task forces and standing committees have regularly been chaired by FCA personnel,” FTI’s report said. This has contributed greatly to the reputation of ESMA as a knowledgeable and credible supervisor at international level. Without U.K. membership, ESMA could lose considerable expertise.”

Similarly, the almost immediate resignation of Lord Hill as EU commissioner has raised doubts over one of his core projects, Capital Markets Union. He was also a strong advocate of the need to maintain constructive dialogue with industry and review the cumulative effect of regulation, as seen in the Call for Evidence launched last fall. Financial markets will hope that this approach continues without him.

FTI also suggested that it is possible that European regulators could deviate from international positions on CCP recovery and resolution without the benefit of Bank of England’s expertise on clearing and active involvement in international work on this issue.

In other areas, the EBA, which is currently based in London, will have to find a new home, with several member states vying for that position.

With outstanding questions such as these, it is little wonder that the market is split on the ultimate outcome for the U.K., Europe and the rest of the world. A survey by Tabb Group found that only 27% of respondents expect the FTSE to up at the end of 2016, with 51% expecting it to be down (20% expecting a drop of at least 10%) and 18% predicting it will be flat.

When asked which model would be the best for the future of the relationship between the U.K. and EU, 22% suggested the Swiss model, 22% the Norwegian model, 11% a European Trade Agreement, 35% mooted a combination and 10% chose another model altogether.

Uncertainty remains the order of the day, with a high proportion of trading venues, vendors, broker dealers and banks unsure of how their revenues will be impacted as a result of Brexit (see "Higher Costs" diagram above).

If one thing is certain, this situation will continue for some time to come.